There may be more votes counted next week, but the results of the Santa Monica elections are clear. What is most clear is that the reactionary turn in 2020 is old news, an artifact of the unique events and despair of that year. The city’s liberal majority has reconstituted itself. I say, “reconstituted itself” and not “returned” because there were notable developments in the liberal vote.

For one thing, the election showed that liberals don’t need alliances with no-growthers to win.

There were four candidates running for Santa Monica City Council who represented traditional, jobs-housing-education-environmental liberalism – Caroline Torosis, Jesse Zwick, Natalya Zernitskaya, and Ellis Raskin. Unfortunately, as I wrote in a previous post, they were competing for only three seats. Collectively the four liberals dominated the vote, but the split vote meant that they won only two of the three.

Two candidates, appointed incumbent Lana Negrete and Residocracy founder Armen Melkonians, were the candidates associated with the “Change Slate.” Three Change Slate candidates won in 2020 running against Santa Monica’s traditional liberal consensus, shocking everyone.

I am not, by lumping Negrete together with Melkonians and the Change Slate, expressing any opinion whether and to what extent Negrete herself identifies with the Change Slate or will vote along with them as a council member. Negrete received endorsements in the election from various organizations (such as Community for Excellent Public Schools) and local political notables who have over the years been on the liberal side. Negrete presents herself as an independent; I doubt if anyone knows how she will vote on the dais. (Perhaps it is significant that she doesn’t list no-growth organizational endorsements on her endorsements page.) However, independent expenditure (I/E) groups more than the candidates created the landscape on which the 2022 election took place. Liberal groups supported Torosis, Zwick, Zernitskaya and Raskin. Grievance-based, reactionary, and no-growth groups and I/E campaigns, such as Santa Monicans for Residents Rights (note the deceptive use of “SMRR”), Santa Monicans for Change, and the Santa Monica Coalition for a Livable City (SMCLC), as well as the no-growth SMa.r.t. group of columnists and Daily Press columnist Charles Andrews, all endorsed Negrete along with Melkonians. They created a de facto slate of the two of them. That’s how the election was fought—those two versus the four liberals. We all got the mailers.

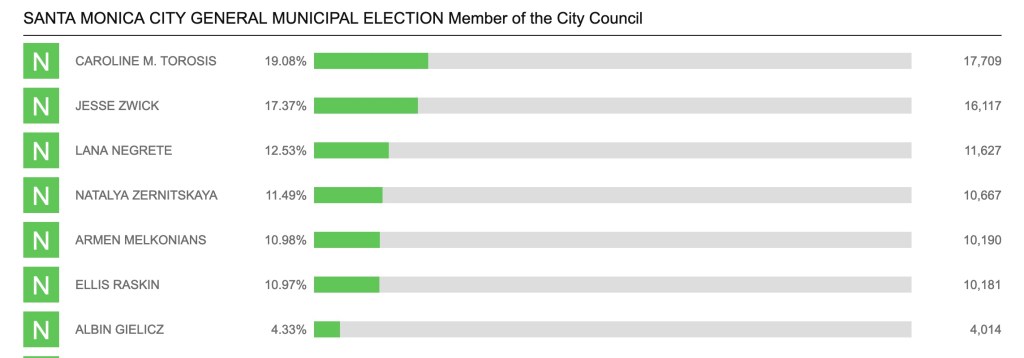

Let’s look at the votes. In the City Council election, Torosis and Zwick, who were endorsed by all the main liberal organizations (Santa Monicans for Renters Rights (SMRR), the Santa Monica Democratic Club, Santa Monica Forward, and UNITE Here Local 11) dominated. By the most recent count (all the vote numbers here are from the totals posted on the County website as of Nov. 25), Torosis has received 17,709 votes and Zwick 16,117. Their totals far surpass the third winner, Negrete, who has only 11,627. Not far behind Negrete is Zernitskaya with 10,667. The top six are rounded out by Melkonians with 10,190 votes and Raskin just behind him with 10,181. None of the other six candidates have received much more than 4,000 votes.

Based on vote totals for the ballot measures, it seems that about 37,000 Santa Monicans voted in the municipal election. That means that Torosis and Zwick each received close to 50% of the vote. Historically that is a good showing. In contrast, Negrete received only about 31% of the vote and Melkonians 28%.

NOTE WELL: The next time you hear someone say or read some column or letter to the editor or Facebook post saying that Residocracy or SMCLC or other NIMBYs represent the people of Santa Monica, remember that Melkonians, with probably at least $100,000 of independent expenditure backing, only got 28% of the vote.

Negrete and Melkonians also had the advantage that their supporters could bullet vote for only the two of them or give their third vote to candidates who had no chance of winning. The four liberals split the vote, but the average vote of the four of them was significantly more than the average vote for Negrete and Melkonians: 13,669 versus 11,147. (Remember also that Negrete had some liberal support, particularly from the education community.) If only three liberals had run they would have won all three seats. (I.e., if the votes of any one of the four had been divided among the other three, all of those three would have won election.)

There was the same result in the School Board election. The three establishment liberal candidates, Laurie Lieberman, Richard Tahvildaran-Jesswein, and Alicia Mignano, all won easily against a grievance slate. Once again, the voters approved an education bond, this time for Santa Monica College.

The main takeaway is the return of the liberals, but what other conclusions can we draw from the vote?

The 2022 vote showed that liberals don’t need NIMBY votes to win elections in Santa Monica. This is contrary to what the leadership of Santa Monicans for Renters Rights (SMRR) has been saying for 40 years. While the positions of the four liberal candidates on housing and development vary somewhat, none of them are what I used to call “Santa Monicans Fearful of Change.” Therefore, it is not surprising that none of the candidates endorsed by SMRR, UNITE Here Local 11, and the Santa Monica Democratic Club (whose endorsements collectively cover all four liberal candidates) also received endorsements from the anti-housing, anti-development element of local politics.

Forgive me a personal note, but I feel vindicated by this. Ever since I have been active in Santa Monica politics, I have been saying two things: that the liberals didn’t need the NIMBYs, and that the NIMBYs had no loyalty to the liberals.

The latter point was easy to prove. As soon as a council member previously supported by the NIMBYs voted for more housing development, the NIMBYs would turn on him or her, something experienced over the years by many council members, including Richard Bloom, Kevin McKeown, Ted Winterer, and most recently Sue Himmelrich.

I couldn’t prove the first point, however, that the liberals didn’t need the NIMBYs, because there were no examples. SMRR always endorsed one or two candidates who also had support from the no growth side. In fact, SMRR’s support for those candidates, which got them elected, was the only reason the no-growth side has had so much power over the decades. SMRR enabled its most virulent haters. Cracks in this façade should have been evident when pro-houser Gleam Davis was the only SMRR endorsed candidate to win reelection in 2020, but it was not until this year’s election that a group of liberals ran against the NIMBY’s active opposition.

The second takeaway from this election is that Santa Monicans love the Democratic Party. Of the four liberals, the two who won, Torosis and Zwick, were the only two endorsed by both SMRR and the Santa Monica Democratic Club. As for Zernitskaya and Raskin, what was the most obvious reason that Zernitskaya did better? Zernitskaya was endorsed by the Democratic Club and not SMRR, and Raskin was endorsed by SMRR and not the Democratic Club. Historically SMRR and the Dem Club have been in sync, with the Club following SMRR’s lead, but this year they diverged, and the Dem Club endorsed Zernitskaya. Turns out that in in Santa Monica in 2022, mirroring the national mood, party loyalty was crucial.

This was borne out also by how every candidate, and/or the I/E campaigns supporting them, wanted to show what good Democrats they were. Resulting in some hilarious mailers, but no need to go into that.

Thanks for reading.