(Note: I haven’t written here about Santa Monica politics since my last blog last summer on the Downtown Community Plan, but I was invited to give a 20-minute talk to the Santa Monica Rotary International Club about the current state of politics here. I gave the talk last Friday, March 23. What appears below is a slightly edited version of my remarks to the Rotary. Much like the travelogues I wrote in the fall about my trips to Norway and Spain, my opinions about the current state of Santa Monica are illustrated—mostly with headlines, to prove to the Rotarians that what I was talking about truly happened.)

Greetings and thanks for inviting to share my thoughts about Santa Monica.

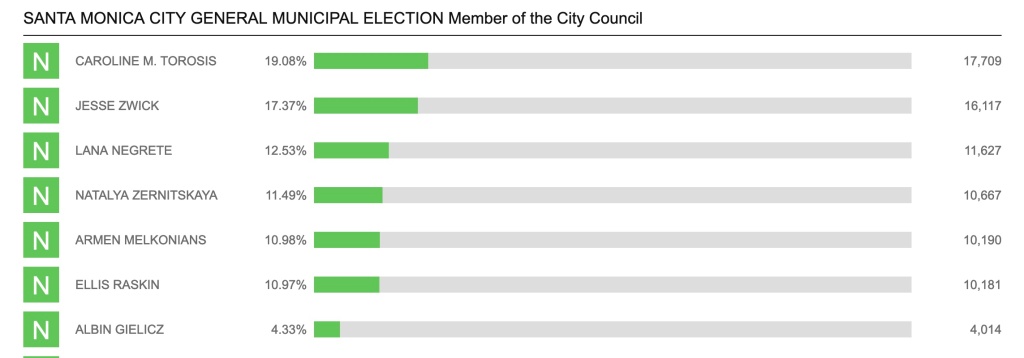

To review my credentials, I’m a former columnist, sometime blogger about Santa Monica, and twice-defeated candidate for City Council. Losing makes me, of course, an expert to talk about Santa Monica politics and issues. In fact, you’ll find during my talk today that losing city council election or two here is a basic qualification for anyone who think he knows how to make Santa Monica government better.

I’m going to start with an update on the development wars. Local governments in California have more control over land use that they have over most issues, and therefore it’s no surprise that development has often been the most contentious issue in local politics, especially in affluent communities where government otherwise does a good job delivering services. Santa Monica has been no exception.

The most recent wave of anti-development activism crested in 2014 with the defeat of plans to redevelop the Paper Mate factory site. This came after a then new anti-development group, Residocracy, had gathered signatures to put the City Council’s narrow approval of the redevelopment plan on the ballot, and the Council revoked its approval rather than have the plan go to a popular vote.

Flush with that victory, Residocracy again gathered signatures, and put a restrictive development measure, Measure LV, on the ballot in 2016. The anti-development wave then, however, hit a seawall when Measure LV lost decisively.

It shouldn’t have been a surprise that LV lost, given that a similar measure in 2008, the “Residents Initiative to Fight Traffic,” (“RIFT”), had also lost.

What the votes on both initiatives showed is that that while there is a large minority of Santa Monica voters who are motivated by the anti-development message—a bit less than 40 percent of all voters who show up at the polls—those voters are, nonetheless, a minority. It’s telling that no city council candidate running on an anti-development platform has ever won election on his or her own, meaning without an endorsement from Santa Monicans for Renters Rights (SMRR), the most powerful political group in the city.

In fact, what we’ve seen in the past two elections is that if SMRR withdraws its support from an incumbent it previously endorsed because SMRR’s anti-development wing sees the incumbent as too friendly to development, the incumbent — Pam O’Connor in 2014 and Terry O’Day in 2016 — nevertheless wins reelection. Meaning that following the views of SMRR’s anti-development wing has cost SMRR two seats on the City Council. It used to be that O’Connor and O’Day owed their election to SMRR; now they don’t.

Getting beyond the politics of development and into the substance of development decision-making, the 13-year process—I have called it “Santa Monica’s long municipal nightmare” —to update the City’s land-use plans finally climaxed in 2017 with passage of the Downtown Community Plan, the “DCP.” We can at least hope that the DCP is the final major plan to come out of the process that started in 2004 with the update to the City’s General Plan. That process was supposed to take two years but took six. Then it took another five years to pass a zoning ordinance to implement the General Plan, then another couple of years for the DCP. Thirteen years—kind of amazing when you think that the plans themselves are supposed to guide the City’s development for only about 20 years. Not to mention that with the defeat of the Paper Mate project, which was the key project for redeveloping the old industrial properties near Bergamot Station, the most important parts of the General Plan update, which focused on the industrial zone, are now irrelevant. We may as well start over now, but the idea of another 13 years is frightening.

The DCP itself was an uneasy compromise. Pro-housing activists did in certain contexts get the theoretical possibility of more development, but by a 4-3 vote the council included financial burdens that developers say as a practical matter will prevent new construction.

In the context of the state and regional housing crisis, which has put on the spot anti-development politicians, especially who those consider themselves to be progressive, the council members who voted to impose the burdens on developers agreed to revisit the plan if it didn’t result in housing being built.

This has led to a de facto truce while people wait and see.

In that regard, three hotel projects in downtown, including this one designed by Frank Gehry, are coming back with plans that conform to the DCP; but there is always discretion, and we’ll see if they get approved.

At the moment there is considerable apartment construction going on under the old standards — this photograph shows the groundbreaking for an affordable housing apartment building on Lincoln that was financed by the developer of a market-rate project — but it’s still an open question whether anyone will build under the requirements of the new zoning ordinance and the DCP. So — stay tuned.

Going beyond the development wars, Santa Monica has a lot of purely political news recently.

For one thing, we’re seeing something that has not been much of an issue in Santa Monica for a long time, perhaps not since the days when Raymond Chandler channeled Santa Monica into his crime novels as the corrupt “Bay City.” I’m talking about political corruption, alleged, possible, and real.

One set of possible cases of malfeasance have been significant enough to garner coverage in the L.A. Times, not to mention investigations by the District Attorney, the California Fair Political Practices Commission (the FPPC), and the School Board. The allegations involve the Santa Monica power couple of City Council Member Tony Vazquez and his wife, School Board Member Maria Leon-Vazquez. While it’s been well known that Tony Vazquez has made his living as a political consultant and lobbyist, it was always assumed that he was careful enough to keep his day job out of Santa Monica. Well, it turned out that companies that he lobbied for to get school contracts applied for work in Santa Monica, and he at least neglected to tell his wife, the School Board member, so that she would recuse herself from voting on those matters, which she didn’t do.

From there the investigation snowballed to include another school board member, and allegations of unreported income and gifts. It’s all being investigated now, so, again—stay tuned.

Then there have been violations of the Oaks Initiative, a law the voters passed about 15 years ago that prevents public officials from benefiting from people or companies who received contracts or other benefits from the City while the official is in office. It’s like a retrospective, rearview mirror bribery law, and the law is complicated because it’s hard to keep track of who received benefits and the time frame for the restrictions. In the past few years the law has ensnared a couple of Council Members, Pam O’Connor and Terry O’Day, who received campaign contributions from disqualified contributors.

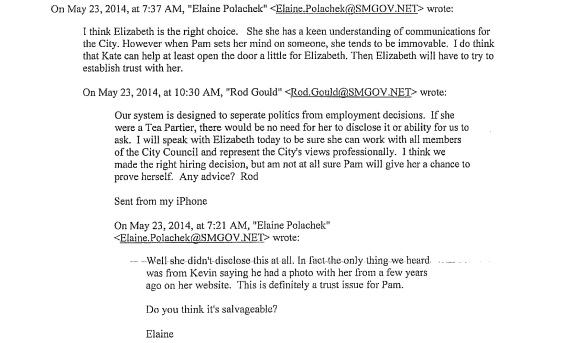

But the most drastic impact of the Oaks Initiative was not on a politician, but on Santa Monica’s former City Manager, Rod Gould. After retiring from the City Gould accepted a job with a company that the City had hired while he was in City Hall, and Gould really paid a price for that. He was sued by the Santa Monica Transparency Project, a watchdog group that pays particular attention to the Oaks Initiative. Gould, saying he didn’t have the resources to fight the suit, settled the litigation by quitting his job and paying the Transparency Project $20,000 to cover their costs.

The most manifestly illegal and corrupt political shenanigans, however, came from the Huntley Hotel, which sits on Second Street across from the Fairmont Miramar. The Huntley opposes the Miramar’s plans to rebuild and in 2012 the Huntley poured money into an extensive campaign to stop the Miramar project. Parts of the plan involved making illegal campaign contributions to City Council candidates and organizing and funding a fake grassroots residents group. It turns out that the FPPC was investigating, albeit slowly, and last year the FPPC hit the Huntley with penalties of more than $300,000: the second largest fine in the history of the FPPC. The Huntley’s scheme also involved the prominent law firm of Latham & Watkins as well as a former Santa Monica Malibu School Board member, Nimish Patel, who had his then law firm conceal illegal political contributions made by the Huntley. The FPPC fined Patel’s law firm $10,000, the maximum fine available to the agency.

I hate to say it, but from the Huntley’s perspective, the money, including the fine, was well spent. It’s six years later, and the Miramar has yet to get a rebuilding plan approved. The Huntley’s financing, organizing and energizing of the campaign against the Miramar revitalized the anti-development movement in Santa Monica, which, after the 2008 defeat of the RIFT initiative, had been relatively quiescent. The 2010 General Plan update had been approved by all the council members, including those from the anti-development side, and even the backers of RIFT generally accepted it. The plan update was the basis for the Paper Mate plan that Residocracy defeated in 2012, after the Huntley had fanned the flames over the Miramar plan.

Meanwhile, although it may seem like nothing ever changes in Santa Monica politics, two major changes to how Santa Monica chooses its elected officials are in the works. I’m referring to district elections and term limits.

As for district elections, School Board member Oscar de la Torre has sued the City under the California Voting Rights Act saying that the City’s at large elections violate the voting rights of minorities, who, because of historical segregation, live predominantly in the Pico Neighborhood. (By the way, like me De la Torre has been a losing candidate for City Council.)

Then this year activists from the Santa Monica Transparency Project—yes, the same group that sued Rod Gould over the Oaks Initiative—began a signature gathering campaign to put a term limits initiative on the ballot.

When it comes to these efforts to change the City Charter, I’m torn. Usually I’m in favor of district voting, so long as there isn’t gerrymandering, not only because it can diversify who is elected, but also because it’s easier for candidates to run in smaller districts. I usually oppose term limits, since in general I believe that anyone should have the right to run for office, and voters are better served by having more choices, not fewer. Also, as we saw was the impact of term limits on the California legislature, term limits can result in too much turnover, giving us legislators who lack experience and knowledge about how to govern.

So those are my usual positions. But as I said, I’m torn, because in Santa Monica the fact is that incumbents can stay on the council for as long as they want. This is not a one side or the other side issue: council members of all political persuasions have remained on the council term after term. So I’m thinking about term limits in a more positive way than usual, although I haven’t made up my mind.

But what about district elections? As I said, I usually favor districts, but I’m not sure we need them in Santa Monica. Why? Because those same council members who get elected over and over are so paranoid about not being reelected, that they try to please anyone who votes, and that includes, for all of them, residents of the Pico Neighborhood. In that sense, the neighborhood is well represented. And, if you include the school board and the college board along with the council, we have a good record of electing minorities. As a result, I don’t see the logic for the lawsuit, although if districting comes, it would make it less expensive and easier for new candidates to run, which would be a good thing in and of itself.

Now that there is, at least for a time, less of a political focus on development, what are the issues, more or less real, that face our community?

How about crime? Rising crime is the issue that Residocracy and its leader, Armen Melkonians (also like me a two-time loser when running for City Council), are trying to use now to gain political power given that development didn’t work. Reported crime, particularly property crime, is up in Santa Monica over the past few years, and there have been some particularly violent crimes, including a murder and a home invasion, in normally low-crime, upscale neighborhoods that have people in those neighborhoods rattled.

However, by historical standards, even with the uptick crime rates are down in Santa Monica. But the historical levels were quite high: I’m speaking as one whose homes have been burglarized twice. Yet I for one don’t sense that people are fearful as they move about the city, not as fearful as the cities I lived in before coming to Santa Monica, namely Philadelphia, Chicago and Boston. But maybe I’m missing something, and I don’t live in the Pico Neighborhood, where there has been gang violence going back decades. Significantly, however, gang violence has considerably decreased over the past four or five years, although in the past year or so there have been several shootings, including one murder, that have the hallmarks of gang violence although the victims are not necessarily gang members.

Let me make an aside here, which possibly ties local politics into national politics. Why is it that a political group that wants to gain power finds that it needs to focus on grievance? Residocracy is explicit that it’s looking for an issue that will motivate voters to vote based on fear. Yet by all measure, Santa Monica is a wonderful place to live — something the leaders of Residocracy will admit, given that they say they are trying to preserve Santa Monica the way it is. Let’s face it, the politics of fear and anger pervade our society, at all levels and, let me make this clear, all sides of every argument use the politics of fear, instead of promoting themselves on the basis of, dare I say it, hope and faith in the future.

In any case, as for crime, the City has hired a new police chief, who was known to have reduced crime her previous job, in Folsom, and so stay tuned on that as well.

Another issue is transit. In a certain sense, with the opening of the Expo line and its great success, this should be the new golden age of public transportation in Santa Monica. Those tens of thousands of Expo riders must mean that more people than ever are using transit in the city. However, those riders don’t count when the Big Blue Bus is tabulating its ridership, and that ridership is down.

This is a regional issue, as the same thing is happening with Metro bus service, but I can’t help being annoyed still whenever I see Santa Monica’ artsy bus shelters (if you can call them that), one of which you can see in this picture. Whenever I see them, which is all the time, I’m reminded that one of our council members, when voting for this design, said it was more important for the bus shelter design to be creative and—quote—whimsical than utilitarian. If you want people to ride the bus, you have to treat them like customers.

Another big issue is the future of Santa Monica Airport.

The City and FAA entered into an agreement a year ago to close the airport in 2029. This timetable disappointed many opponents of the airport, including many like myself who want to turn the land into a big park, especially because if previous agreements with the FAA had been written less ambiguously, the City could have closed the airport in 2015. But as a settlement of confused litigation the deal made sense.

And because the agreement allowed the City to shorten the runway, jet traffic has been drastically reduced—down about 80% from a year ago.

And another 12 acres have been opened up to park expansion. Because the City has taken over leasing at the airport, the City is making a lot of money from rents that will pay for some park construction and ultimately operating costs for the big park.

But let’s face it, the big issue confronting Santa Monica as well as the rest of the region is homelessness, and that’s not getting better.

The title of this talk includes the question whether, as the immortal Tip O’Neil once said, all politics are still local. There’s no question that with homelessness you finally get the answer, which is — yes and no. Yes, because the attitudes of most voters are still made up most of all with how they see their own daily reality. But no, because those realities, whether they are homeless people living on the streets of Santa Monica, or abandoned factories in the Midwest, are products of decisions beyond the purview of any particular local government.

Homelessness, which not only is a moral disgrace but also costs the City of Santa Monica millions in direct and indirect costs each year, is the product of a statewide housing crisis, state and national policies on treatment of, and funding for, the mentally ill, a catastrophic national policy on drugs, and other forces beyond the purview or pay grade of Santa Monica’s elected officials and staff.

Yet, the lack of ultimate power to effect change does not diminish our responsibility as citizens to continue to seek change. We need to solve the homeless crisis, or risk failing as a society.

Thanks for reading.