I was traveling in Italy earlier this month so thankfully I wasn’t around when the Santa Monica City Council had the mother of all nightmarish meetings. The meeting began the evening of Oct. 10, but the council was in closed session for hours and the public meeting didn’t start until late. Then the council stayed up until 4:00 a.m. to vote on what kind of public process to have for developing plans for when Santa Monica Airport closes at the end of 2028.

It was ugly. The “Make Santa Monica Great Again” crowd went way over-the-top crazy over a plan to expand public process by empowering a “grand jury” type group of randomly selected, but demographically representative residents to advise the City Council on what to do.

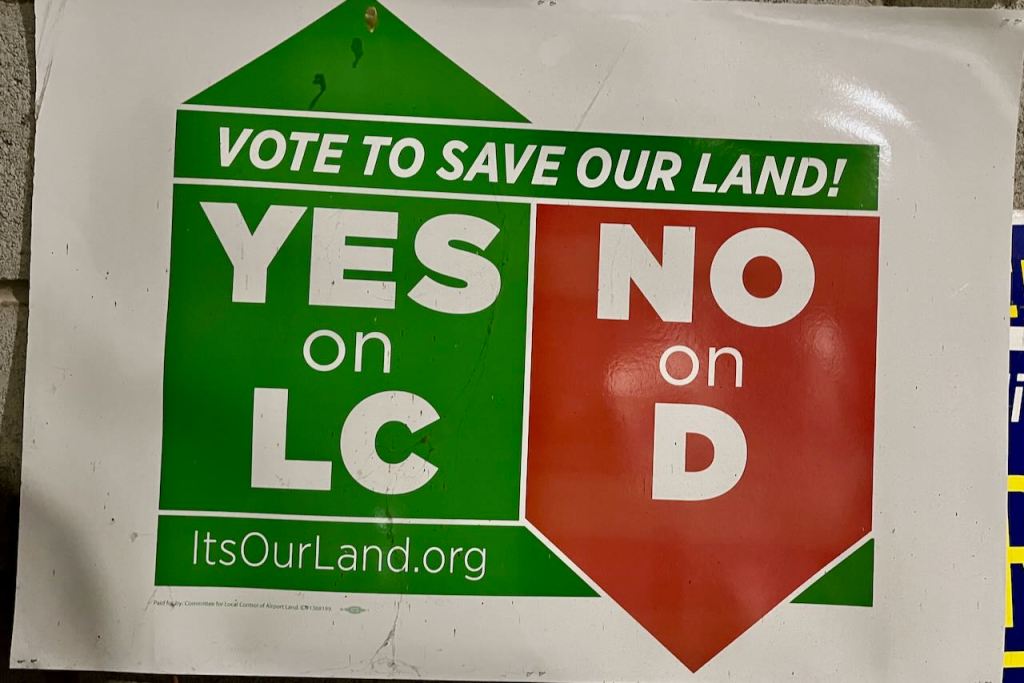

Staff had proposed the new plan after the council had directed it to do so, a fact ignored by some forgetful council members. The plan got caught up in anti-development paranoia, as MSMGA residents saw it as a plot to develop airport land. (This from the same residents who usually direct their paranoia at staff and City Council; one might think they would have more trust in 40 randomly-selected residents than the decision-makers they usually despise.) While the local outrage machine manufactured most of the hysteria, some was unfortunately stimulated by a staff report that seemed to forget that the default for the airport land is to turn it into a park in accordance with Measure LC. If you want to know more of the gory details, here are links to two articles in Santa Monica Next that unpack the false statements made against the plan: one from before the meeting and one from after.

There are lessons for everyone to learn.

For those worried about development at the airport, please – relax a little. However staff writes its reports, needing to sound evenhanded when it comes to alternatives, Measure LC still governs. No, a 40-person committee of randomly selected residents would not have had final decision-making authority over the airport land. Not even the City Council would have final authority if it wanted to propose something inconsistent with LC. Anything inconsistent with LC needs a vote of the people.

For those who want housing at the airport, take this over-reaction seriously even if it was not based on reality. This goes for staff, too, which may need to be agnostic about what happens at the airport, but which needs to be careful about the language it uses. The biggest danger to the future of the airport land is for the aviation industry to mount another initiative, like their Measure D in 2014, to stop the City from closing the airport. The biggest danger of such an initiative passing is if the aviation industry can whip up fear to persuade the anti-development element of Santa Monica politics that if the airport closes it will be replaced with development. Most anti-development residents live far enough from the airport that they don’t care if it closes.

Speaking for myself, as someone who for 30 years has pushed for Santa Monica to build more housing, the airport is simply not a good place for housing. Housers should look elsewhere. The airport land is never going to be convenient for transit or walking to shopping. Meanwhile, residents need parks, and every square foot of open land at the airport is a special and precious resource, purchased a century ago with a parks bond. While it would be possible, under LC, to convert existing structures into housing, those structures are better suited for what they are being used for now: offices that the City leases to businesses. The City will be able to use the revenues from the leases to build and operate the park. (See my prior blog on how to do this.) Affordable housing is needed in Santa Monica but it will not generate revenues to build a park – affordable housing needs its own subsidies.

My advice to housers who insist on locating housing at the airport: talk to the Santa Monica College (SMC) Board. SMC not only owns the Bundy Campus, but also owns land along Airport Avenue that is not subject to LC. Over the years, heedless of the impact on the local housing market, SMC has expanded by enrolling many international and other out-of-district students who need housing because they can’t or don’t live at home. SMC can build dormitories without parking for students, who can be connected to the SMC campus and to transit by SMC shuttles. They would thus neither add to traffic nor need a direct connection to transit.

My advice for the City Council, aside from not making decisions in the wee hours – please, help dial down the rhetoric, don’t amplify it. You are supposed to know better. The City is embarking on the biggest infrastructure project in its history. It is a great opportunity. It will not succeed if elected officials play into the fear game.

• • •

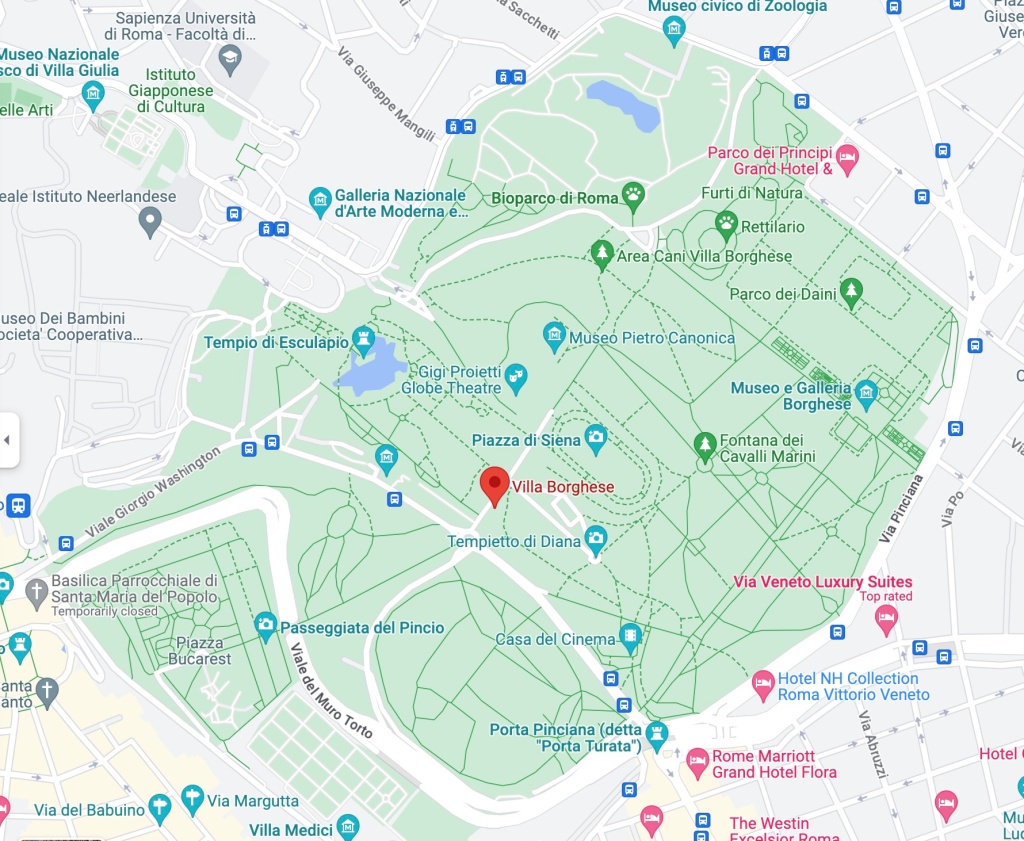

Meanwhile I want to report on something inspiring. When in Rome a couple of weeks ago I did what the Romans do – I took a long stroll in the Villa Borghese Gardens. The Villa Borghese is one of the great parks of Rome – of the world, in fact. Originally an aristocratic estate, built out over centuries, the government purchased the property in 1902 and turned it into a park.

How big is the Villa Borghese? About 198 acres, not too much bigger than the 160 or so acres of open land at Santa Monica Airport.

The Villa Borghese demonstrates that a great park need not be over-designed. Most of the park consists of winding paths through a landscape that is beautiful but, so far as I could tell, not irrigated. (The Roman climate is similar to ours.)

Within the park are several museums, including the world famous Borghese Gallery and the Villa Giulia, Italy’s great Etruscan Museum. There is also a reconstruction of the Shakespeare’s Globe Theater, and a cinema, and Rome’s zoo. There are playing fields and playgrounds. But in no way does the park feel cramped or over-programmed – 198 acres is a lot of land (as is 160).

There are a number of lessons to learn from the Villa Borghese. As I already said, but I’ll repeat it, a great park need not be over-designed. When it comes to the Airport Great Park, let’s keep it simple, and get it built. As I wrote in my previously-mentioned earlier blog, establish a budget first and stick to it.

Another lesson is that great parks can evolve over time. The Villa Borghese has evolved over centuries. Let’s get a basic version of the Airport Great Park built, and let future generations make decisions about whether they want to add features.

Thanks for reading.