It has been a few weeks since the Santa Monica City Council voted to begin planning a great park to replace Santa Monica airport, and I have been thinking about how best to do it.

As the staff report prepared for the City Council says, the right first step is to evaluate all aspects of the site, including environmental conditions, infrastructure, transportation, cultural assets, etc.

However, beyond that evaluation I am concerned that in the interest of planning something for the ages, the process may deliver a plan that makes it harder or even impossible to build something in the near term. Everyone loves to quote Daniel Burnham’s “make no little plans,” but Santa Monica has not had success in recent years realizing “big plans.” Consider the 2010 LUCE, or the Bergamot Station plan, or the Fourth and Arizona plan, or the abortive planning for the Civic Auditorium site. Going back further, consider the 1994 Civic Center plan, which was approved overwhelmingly by the voters, but then scaled back and only partially implemented.

What typically happens is that the City begins a planning process by hiring consultants to run it. The consultants research the issue and organize lots of outreach. The consultants present their research and analysis and receive all kinds of visions from the public. The Planning Commission usually oversees the process, sometimes in consultation with other commissions. There are many hearings, spread out over years.

Ultimately the consultants write up a beautiful plan. (The plans often win awards.) There are more commission hearings. Then the City Council approves the plan after extensive hearings of its own, often with substantial modifications.

But when it comes time to implement the plan, all that will get thrown out the window when a vocal contingent, who either ignored the process or didn’t get what they wanted, objects. The council, whose members may have changed during the (many) years it took to develop the plan, backs down and doesn’t approve anything to be built, or scales the plan down drastically. (Note to those council members who admonished staff to devise an open and inclusive planning process: no process can be inclusive enough to include those who are going to oppose the plan no matter what.)

I am concerned that the same fate could befall plans for the great park on the airport land.

My fear is that the process will put design first (“no little plans”), and budget second, resulting in a plan that is doomed from the start. You see this lurking as a major concern in the staff report, which is full of worries about how the new park will be financed. We should not be building Tongva Park at 30 times the scale, yet I suspect that is where we will end up once everyone says what they want.

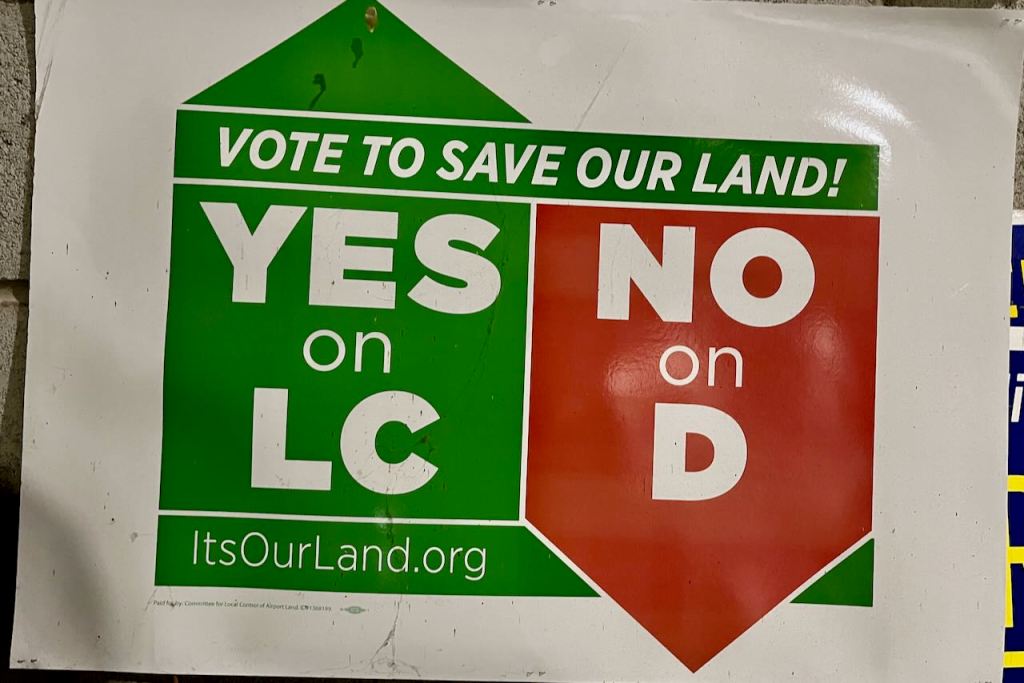

This concerns me because (A), I want to see a park built in my lifetime (and I’m 70!), and (B), I know that the aviation industry is waiting to jump in with a ballot measure to preserve the airport if they see confusion and worry about the park and if they can scare the public into thinking nothing will be built unless there is hyper development to fund it.

These worries about financing the park are unnecessary. Santa Monica already has enough money to build a fine park. The airport properties generate $20 million a year in income for the City, mostly from non-aviation businesses that lease office space in buildings that the City owns. The City has owned these buildings forever but until 2015 they were under the control of aviation businesses that subleased to non-aviation businesses. So long as the airport functions as an airport, these rents can only be used at the airport. Once the airport closes, they will be available to fund a park.

The staff report suggests the need for public/private partnerships, which is bound to scare residents concerned about development. The City, however, already has a lucrative public/private partnership: the public part is the City’s ownership of the land and the buildings, and the private part is the revenue the City receives from its lessees.

How much money does the City have already to build a park? Let’s assume that there is $20 million a year to work with. (This amount will increase when aviation uses are replaced by businesses that pay higher rents, and because of inflation, but let’s deal with today’s numbers.) If the City issues a 20-year $200 million revenue bond at 3% interest (typical for a municipal bond), the annual payment to amortize it would be approximately $14 million. That would leave $6 million a year for maintenance of the park.

Meaning, that without raising any more money, Santa Monica has $200 million to build a park and $6 million a year to maintain it. Note that the City would not have this money but for the fact that it is closing the airport, meaning that the money does not deplete some other line item in the City’s budget. (The City will also have accumulated significant cash from these leases by the time the airport closes, but the disposition of these funds depends on negotiations with the Federal Aviation Administration. To be conservative I am not including them in my calculations.)

If by 2028 there are additional committed funds, such as from other governmental agencies for environmental clean-up, or transportation or other infrastructure, or from philanthropic donors, then those funds can be added to the pot. When the City Council next visits this topic, however, it should direct staff to plan for a park that costs no more than the money that can be raised from a revenue bond or is otherwise committed. Nothing speculative.

This doesn’t mean that the future park would be limited to this amount. Parks evolve over time, and you never know what other governmental funds (county, state or federal), or philanthropy, might become available in the future. The City, however, must begin the process with a plan it knows it can realize with the money it has. The City should tell residents, that no matter what fears the aviation industry arouses, the City can have a groundbreaking for a fully-financed park on Tuesday, Jan. 2, 2029. (See you there!)

In other words, keep it simple. I was impressed with something Mayor Gleam Davis said in her recent State of the City address, namely: “We can accomplish great things but only if we spend our limited time and resources in a disciplined and targeted way. If we let ourselves get distracted, we set ourselves up for failure.” That should be the footnote when anyone quotes Burnham.

Thanks for reading.