After 25 years at the head of Downtown Santa Monica, Inc. (DTSM; previously known as the Third Street Development Corporation), Kathleen Rawson is stepping down.

In case you don’t know, DTSM is a public/private partnership between the City of Santa Monica and downtown property owners to operate a business improvement district (BID). The district initially consisted only of the area surrounding the Third Street Promenade, but it now includes all of downtown Santa Monica.

Twenty-five years. Santa Monica is a city where city managers, chiefs of police, superintendents of schools, and other high-ranking civil servants typically stay for, or survive, five or six years at most. A tenure of 25 years in a job with unique pressures that come from balancing the interests of anxious property owners, their demanding tenants, and politicians who need to please voters, is something that can only be described as marvelous, as in “something to marvel at.”

All hail, Kathleen. We wish you well as you head to the Hollywood Partnership to paint a picture on an even bigger canvas.

In the meantime, Rawson’s departure provides an opportunity to look back at the history of downtown Santa Monica.

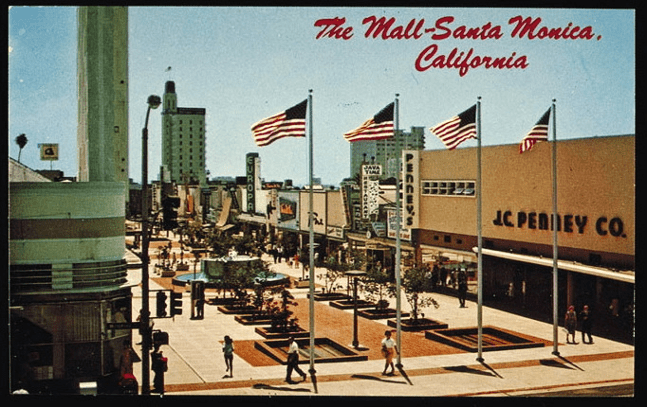

I’ve been closely watching (and using) downtown for about 40 years. Even before the City brought in movie theaters and created the Promenade as we know it today (in 1989), back in 1981 I was on the board of the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble. We tried to get property owners to support building a theater on what was then called the Third Street Mall. The Mall was desolate and we thought a theater would help revive it. As was shown a few years later with the movie theaters, we had the right idea. Unfortunately, we did not have the right program to make it happen. (We wanted property owners to lease us land for zero rent, and that wasn’t going to happen.)

Then in 1994 I moved my law office downtown. Initially I found an office in the Clock Tower Building on Santa Monica Boulevard, just west of the Promenade. (My occupancy was delayed, by the way, by the Northridge Earthquake.) New owners of the building emptied out us tenants in 2001 to rehab it into what became one of the most sought-after addresses in Silicon Beach. Ultimately, I found a new office in another 1920s building, the Central Tower Building on Fourth Street. I’ve been in that office for almost 20 years.

In 2003 my parents moved from Philadelphia and rented a two-bedroom apartment in one of Craig Jones’ new buildings on Sixth Street. My mother died in 2007, but my father lived in the apartment until he died in 2019. Through them I learned about what it was like to live in the new residential downtown that new zoning that the City enacted in the ’90s made possible. (They loved it.)

Forgive me if I feel like I have not only some knowledge of, but also a proprietary interest in, downtown Santa Monica. (Hey: as a business owner downtown, I paid double business taxes to support DTSM’s activities!)

The foundation for the initial success of the Third Street Promenade was a combination of factors that predated Kathleen Rawson’s stewardship of DTSM. Those factors included: the Hollywood studios’ finally breaking the Westwood monopoly on first-run movie theaters on the Westside, which enabled movie chains to build theaters in Santa Monica; visionary leadership from city government, notably from Council Members Dennis Zane and the late Herb Katz, which allowed those theaters to be built only downtown; and excellent urban design from Boris Dramov of ROMA Design Group.

Rawson, who was brought in in 1997, made downtown Santa Monica work in a way that both reflected and managed its context. And that context was and is urban, the legacy of downtown’s origins as the central business district for a satellite factory town that had a working fishing pier and honkytonk amusements to boot. Santa Monica was a blue-collar town that like so many was ripped apart by a freeway, which local boosters thought would bring investment to downtown Santa Monica but instead made it increasingly irrelevant. The City expected to solve downtown’s problems by demolishing some crucial blocks downtown to build an indoor mall, Santa Monica Place, but that was then the final blow to the old Third Street Mall, which sunk into decrepitude.

When the Promenade opened in 1989 many were tired of the suburban retail experience – of malls. I dislike using “authentic” to describe any built place, but people wanted authentic, not artificial, experiences. Neither the movie theaters nor Dramov’s design altered the fact that the Promenade and downtown had not sprung full grown from the heads of architectural descendants of Victor Gruen.

Downtown Santa Monica was undeniably authentic because it was open to all. Which brings up the shame of our society, homelessness. For the 40 years I’ve been around, Santa Monica’s treatment of the unhoused has always been controversial, from every direction. It goes without saying that in our wealthy country homelessness should not exist. We can blame ourselves for the fact that we do have homelessness. In the meantime, whenever things are not going well downtown, you can be sure that homeless people will be blamed for whatever the perceived problems are. Yet it was antiseptic Santa Monica Place, the only place in downtown from which homeless people were excluded, that had to reinvent itself, by making itself more open and better connected to the Promenade, to keep pace with the level of retail sales on the Promenade.

Meanwhile, for those who believe that Santa Monica’s approach to homelessness has made the problems the unhoused create for the housed worse: well, just consider that Santa Monica does not have the sidewalk encampments that have sprung up in Los Angeles. Santa Monica’s approach has been not to criminalize homelessness, but to provide services and to try to build more housing, all the while not allowing the condition of being homeless to justify antisocial behavior. This has been DTSM’s philosophy, as exemplified by its Ambassador program, which Rawson instituted about ten years ago. (It is also the philosophy behind replacing Parking Structure 3 with housing; let’s do it!)

Perhaps the biggest tribute to Rawson’s management of DTSM has been the expansion by the City of DTSM’s purview. Originally, the Third Street Development Corporation was focused on only the blocks around the Promenade and collected assessments from only that area. Then the geographical scope was extended from Wilshire to the freeway, and Ocean Avenue to Seventh Street. Later, when the Expo line opened in 2015, the assessment district was extended to include Lincoln Boulevard and additional areas around Colorado Avenue. Since 2018, the Ambassador program has been extended even further, to include Palisades, Reed and Palisades Park. (As a mark of the expansion of Rawson’s responsibilities, the DTSM budget increased from $800,000 to $9 million over the past 25 years.)

This expansion took place as downtown Santa Monica evolved, as living places always do. About 4,000 people now live downtown, a big change from 30 years ago. If you walk Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Streets, where most of the new apartments are, you see the neighbors out and about. They shop in local stores and, especially, eat in their neighborhood restaurants (or, rather, in these Covid days, they eat outside of them).

What I have admired about DTSM’s approach (which I assume is Rawson’s approach) is a respect for the unpredictability of the urban context, while recognizing that a little management of it can go a long way. This is the approach of the Ambassador program, and was also the approach behind the Street Performer Ordinance. You can see the approach in the new restrooms in Parking Structure 4 (how often in America does a city provide that basic amenity?).

Meanwhile, ICE, the immensely popular ice-skating rink that Rawson initiated (inspired by growing up in Minnesota) and actions like opening the Promenade for outdoor dining when Covid hit, or instituting a family-friendly PRIDE festival, reflect an attitude that public areas in a downtown should not be static, that they are flexible spaces, not built and programmed for specific functions.

What’s next for downtown Santa Monica? Even before Covid, the brick-and-mortar stores on the Promenade were feeling the pressure from on-line retail the same as retail everywhere. Stores were closing, there are vacancies, and rents are declining. With Covid, the loss of free-spending international tourists has been devastating. Rawson’s next plans were for downtown to pivot more towards entertainment, events, and dining. (Disclosure: I’m on the Board of the Jacaranda Chamber Music series, which has presented concerts downtown at the First Presbyterian Church for almost 20 years; Jacaranda has been in discussions with DTSM about presenting one or more outdoor concerts.)

One thing we know is that downtown Santa Monica will not stay still. It will continue to evolve. Let us hope that the DTSM board will find a successor to Kathleen Rawson who is as capable as she: capable enough to survive 25 years in a tough job.

Thanks for reading.