If you have been reading me since I started writing my column in the Lookout News 26 years ago, or if you’ve been reading this blog since I began writing it in 2013, or if you remember that a very slow growth City Council dropped me from the Planning Commission in 1999 because I was too “pro-development,” or if you followed my ill-fated campaigns for City Council in 2012 and 2014, when I was tagged as “in the pocket of developers,” you know that I have consistently advocated for more housing in Santa Monica, as much as anyone else involved in Santa Monica politics going back more than 30 years.

I have also been an advocate for the conversion of the Santa Monica Airport land into a park. At a candidate debate in 2012 we candidates were asked what would become of the airport land if the airport should close. I replied that it should become a park; I’m flattered that some say that that comment kicked off the movement to turn the airport into a park. I am on the boards of both the Santa Monica Airport2Park Foundation and the Santa Monica Great Park Coalition. (But the views expressed here are mine and not necessarily those of the organizations.)

I’ve also always been a strong supporters of unions, particularly of UNITE HERE Local 11 and its efforts to organize hotel workers in Santa Monica’s crucial hospitality industry. When I ran for City Council in 2014, there was nothing I was more proud of than receiving UNITE HERE’s endorsement. (For what it’s worth, I hope unions get back into the business of building cooperative housing like they did last century, particularly in New York.)

Okay, enough about me.

I am writing this blog to express my strong opposition to the ballot measure that UNITE HERE, along with certain members of Santa Monicans for Renters Rights (SMRR), and other well-intentioned advocates for affordable housing, have proposed to amend Santa Monica’s General Plan so that it would require that 25 percent of the land at the airport be used for 3,000 units of affordable housing.

Proponents are now gathering signatures for the measure. Please don’t sign it.

If passed, the measure would greatly diminish the Great Park that we need: Santa Monica is seriously under-parked and will become more so as we build more housing elsewhere in the city. Furthermore, the measure would locate a neighborhood of apartments for mostly low-income households in an isolated part of the city.

I could leave it at that, since no matter how the measure would have been written, for the reasons just mentioned I would oppose it.

But the houser in me can’t keep myself from looking at the measure on its own terms. As a planning document, it fails. It is ballot-box planning of the worst sort, aiming to be comprehensive, because its drafters don’t trust the political process, but then failing every test of good planning. Its financing plan is a mystery. As ballot box planning, it wouldn’t be amendable without another vote. It is so detailed it is doomed: no plan etched in stone can cover every eventuality.

Last year in a blog I wrote why the airport land is an inappropriate site for housing. (“We already have a city. What we need is a park.”) I focused then on one of the potential scenarios staff and the consultants had devised for the airport’s future, one that included a new neighborhood. Unfortunately what I said about that proposal is the same as what I would say about the vision contained within the current ballot measure, namely, “I can’t help but wonder: is this plan an homage to modernist superblocks from the 50s or to New Urbanist new towns of the 90s?”

Except that it’s worse, because it would all be income-restricted, at least half low-income (80 percent of median income and below) and most of the rest restricted to 120 percent of median. Didn’t we learn from the 50s and 60s that it is not good planning to concentrate low-income people in an out-of-the way superblock?

There is no precedent for planning for any development in Santa Monica by means of a ballot measure, let alone a development of 3,000 apartments and accompanying commercial uses on nearly 50 acres of publicly-owned land. Citizen-initiated ballot measures like this one do not require environmental or other review. In any other case even a small amendment to the general plan would undergo considerable preparation, review and discussion before even coming to a vote in our City Council.

The measure’s proponents are asking the voters of Santa Monica to sign onto the measure without having sufficient knowledge about what the implications of the proposal would be. The expression “to purchase a pig in a poke” comes to mind.

Let’s look at some of the issues.

Cost and financing. It’s been reported that the median cost to build a unit of affordable housing in Los Angeles County is upwards of $600,000. The base construction cost for 3,000 units of affordable housing might therefore be close to $2 billion, or even more.

Moreover, the $600,000 figure does not include the cost of infrastructure, since affordable housing is generally built in developed areas. Other than for the runway, most of the airport land has never been developed. Not much of the airport has the infrastructure, such as water, sewer, roads, power, etc., to support housing development. The airport doesn’t have schools or libraries or other public facilities either. In this sense, the proposal does not qualify as infill development.

If the cost of building the 3,000 units and required infrastructure would make the goals of the ballot measure infeasible, that will result in paralysis. This paralysis over the housing development would stymie development of the rest of the airport land as a park. I have this concern because by the initiative’s terms, its amendments to the general plan can only be changed by a vote of the people and the building of the housing is mandatory. The measure states: “It is the policy of the people of Santa Monica that the City Council should take all steps necessary to ensure that 3,000 units of Community Housing are developed and occupied on Airport Land.” What does “all steps” mean?

My fear of paralysis (which is shared by the pro-housing group Santa Monica Forward, which also opposes the measure) is not unfounded. Since 2014 when Santa Monicans voted overwhelmingly to defeat the aviation industry’s attempt to make the airport permanent and to support conversion of the land into a park (Measure LC), there has been rare consensus, or near consensus, on what to do with the land. No one has been elected to the City Council who opposes closing the airport and building a park there. But the ballot measure would convert this irreplaceable public asset into another site of contention, like the Civic Auditorium or Bergamot Station or 4th and Arizona, where over decades it’s been impossible to make decisions about the future of the sites.

In other ways the measure is simply vague. Uncertainty is another source of paralysis.

For instance, consider the 25/75 split. The ballot measure requires that 25 percent of the airport land be used for the 3,000 units of housing and that the other 75 percent of the land be used for park and other uses already allowed for under Measure LC. A considerable amount of the airport land, however, is in use for other purposes, such as for offices leased to businesses. Would the land used for those purposes come out of the park side of the 25/75 equation or the housing side? Or be “taken off the top?” The measure doesn’t say.

Then there is commercial and other development. While the ballot measure invokes the principles of New Urbanism by including “community-serving amenities,” including grocery stores, cafes, “small neighborhood shops,” etc., all “integrated into the primary Community Housing uses,” there has been no analysis of what would be needed in the new neighborhood and what could be supported by the purchasing power of the people who would live there.

Since the new neighborhood would be relatively isolated, it would need to be largely self-sufficient unless we expect every household to have a car. For instance, how big would a grocery store need to be to serve these households? Who would build and operate it? What would be the cumulative purchasing power? By concentrating 3,000 affordable units together, there could be a “food desert” despite the best intentions of the initiative’s drafters.

And what about schools? Strangely, although the measure mentions the possibility of including libraries as “public/community uses … that are local-serving and encourage foot traffic,” it doesn’t mention schools, preschools, childcare, etc. According to Google Maps, it’s an 8/10 of a mile walk from Atlantic Aviation, on the very northern edge of the airport, to the nearest public elementary school (Grant), and a 1.2 mile walk to John Adams Middle School.

Strange that such a detailed measure purportedly designed to provide housing for low-income working families says nothing about kids. A typical problem with ballot box planning.

As I said upfront, this initiative is unprecedented. Yes, I want all the available land to be a park and I would oppose any measure that takes land from the park. But that doesn’t change the fact that the voters of Santa Monica are being asked to decide a highly complex issue without the kind of analysis that is necessary.

If asked to sign the petition, please politely decline.

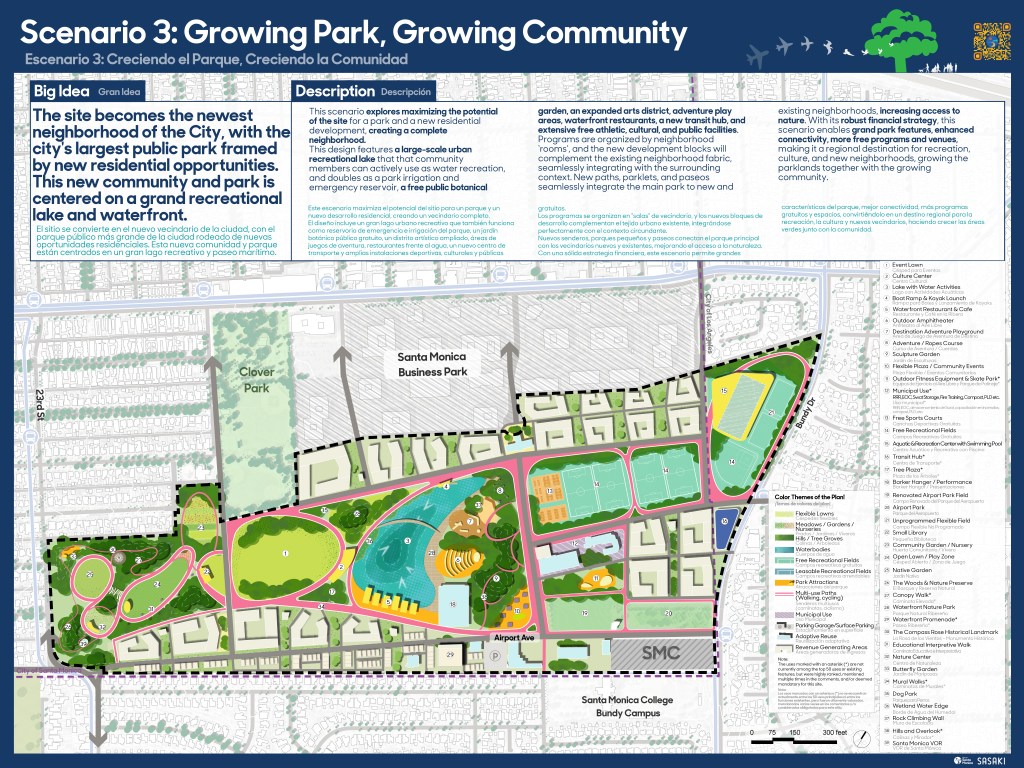

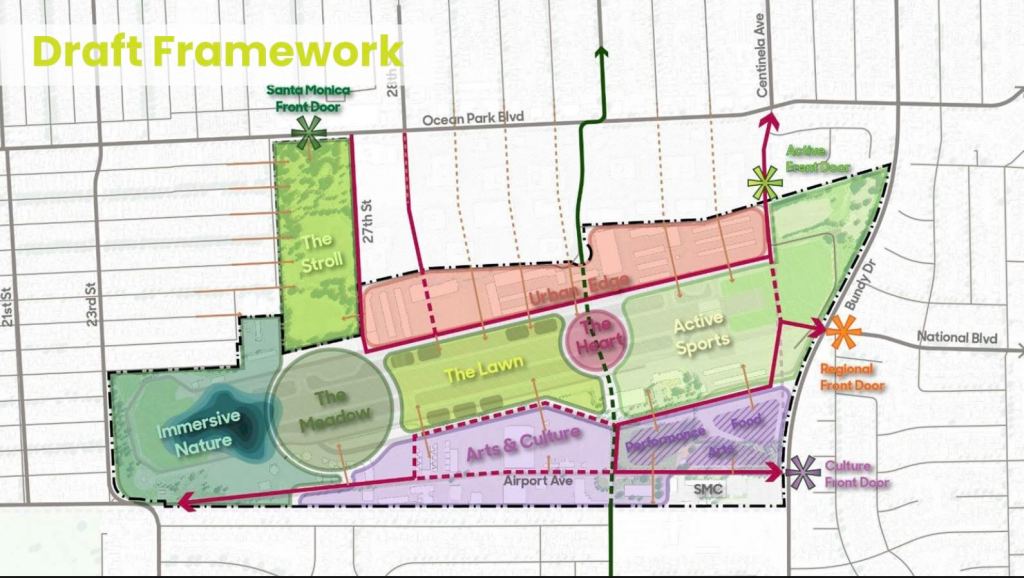

Meanwhile, the City’s planning for the Great Park at the airport advances. The City has now released an exciting “Framework” to guide future, more detailed planning, and is seeking public comment before the City Council considers it in probably early May. The Framework divides the land into districts, as shown in this diagram. As I said, it’s exciting.

Thanks for reading.