The Los Angeles Times ran an article in today’s paper about how developments at Santa Monica’s Civic Center, both public and private, are now coming to fruition. This has been evident to anyone who has recently traveled on Main Street or Ocean Avenue south of the freeway, but it’s worth noting that both the City’s two new parks, Ken Genser Square and Tongva Park, are going to open soon, as well as the Related Companies’ mixed condo and affordable housing developments south of Tongva Park and along Ocean Avenue.

It’s also worth noting that these projects result from 25 years of planning, planning that began in the late ’80s when the City formed a task force to determine how much of what kind of development to permit in the Civic Center. The task force’s conclusions led, in 1993, to a public design process and the creation of a “specific plan” for the Civic Center.

Reading the article in the Times, I couldn’t help but reflect on the current process to develop a specific plan for downtown Santa Monica.

One thing that was the same in 1993 as it is 20 years later was that the plans to develop the Civic Center engendered considerable controversy. People ask me if I have ever seen people in Santa Monica as “angry” as they are now about development, and my reaction is, “Hell yes.” The opposition to the Civic Center Specific Plan (CCSP) was fierce. People got so riled up that even when the City Council, which then included anti-development stalwarts Ken Genser (for whom the plaza in front of City Hall has now been aptly named) and Kelly Olsen, voted 7-0 to approve the plan, opponents, who were worried the development of the Civic Center would cause gridlock, gathered signatures and put the CCSP on the ballot.

In the June 1994 primary election, the voters of Santa Monica approved the plan in a 60-40 landslide. Opponents of the CCSP will tell you that they lost because they were outspent, but they had a lot of factors in their favor, including the fact that one of the chief opponents of the plan, Tom Hayden, who was then a popular local politician, was on the June ballot running for the Democratic nomination for governor, and the election was a primary with lower turnout than a general election. Going into the election the opponents expected to win, because in an election just a few years before they had successfully defeated a City Council-approved plan to allow restaurateur Michael McCarty to build a hotel on the beach.

But the development and passage of the CCSP is only half the story. What happened since, what happened in reality, tells us a lot about why planning is . . . well, planning.

Of the 45 acres covered by the CCSP about one-third were owned by the RAND Corporation. One motivation for developing the plan was to determine what RAND, one of the most important companies in Santa Monica, could do with its land. RAND wanted to rebuild its headquarters, but also wanted to make some money developing its property. For this purpose it joined forces with a developer, the Janss Corporation. (Janss had a long history – it was the original developer of Westwood.)

Santa Monica voters approved the CCSP in 1994, but the approval came late for RAND, which had begun the planning process with high hopes in the boom years of the ’80s. The ’90s were bleak years for Southern California, a time of riots and crime, a drastic drop in real estate values, and, yes, an earthquake. RAND and Janss tried to develop the property, but Janss fell into bankruptcy over losses from a development in downtown Santa Monica (in the real world, developers do go bankrupt), and RAND ultimately threw in the development towel and sold most of its land to the City.

This resulted in the City revising the voter-approved CCSP and a drastic reduction in the amount of development anticipated in the plan.

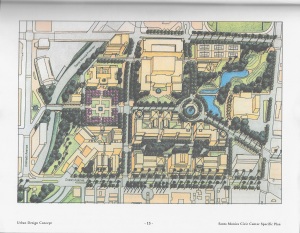

Below is a copy of the “Urban Design Concept” that was included in the CCSP (which was, in its entirety, sent to voters with their sample ballots) As you can see, the proposed development was much denser than what is being built today. The reason is that under the CCSP RAND had the right, under a development review process, to expand its facilities from its existing 300,000 square feet to 500,000, and to build another 250,000 square feet that could either be offices for rent or housing.

After the sale to the City of most of its land, RAND decided, for its own purposes, to build, on the land it retained, a new headquarters that was only a few thousand square feet bigger than the 300,000 square feet of its old buildings. The right to build the 250,000 additional square feet devolved to the City.

While at first during the process to revise the CCSP it looked like the 250,000 square feet would become housing, at the very end of the process, to please residents who wanted more open space, this housing was dropped from the plan. That’s why Tongva Park is so much bigger than the park that was originally intended to be a buffer between a new RAND headquarters and the freeway. (One reason the park was smaller in the 1993 CCSP with more development around it was that planners were worried that the park, given its location, would need help being “activated” – this may yet turn out to be a problem.)

Contrary to the popular narrative that against the will of the people politicians and planners have allowed Santa Monica to be overdeveloped, in the case of the Civic Center the opposite is true. Nearly 450,000 square feet of development, including around 250 units of housing, was dropped from a plan the voters approved overwhelmingly.

Thanks for reading.

Pingback: Who’s a Victim? | The Healthy City Local

Frank, could you also enlighten us on how the tallest building in Santa Monica, the one at the end of Wilshire, was approved?

Bob — that was before my time and so I don’t know. But I doubt it was controversial — it was the headquarters for one of SM’s most important businesses, General Telephone, and the architect was Cesar Pelli, so it must have been seen as a high-class project benefiting the city. How does the saying go, “autres temps, autres moeurs?”

Hmmph. I didn’t know that. The details have been obscured over time for sure.